An Elementary School Schedule that Promotes Student Learning

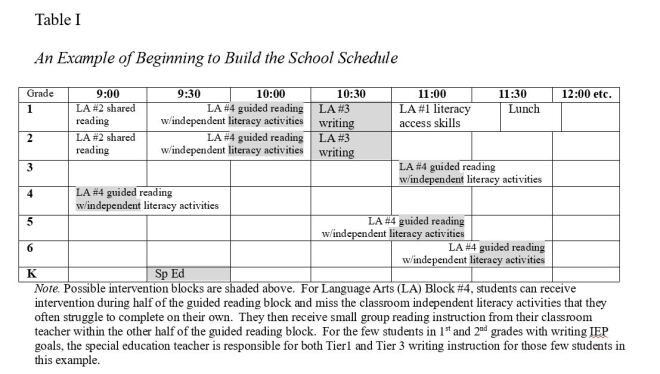

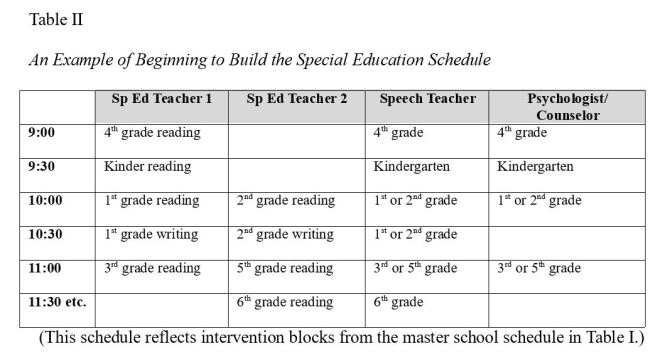

[Editor's note: Refer to Table I and Table II above for a visual representation of the author's scheduling practices.]

Spring is a great time to consider some high-leverage work that will help set up your school for success in the next school year.

You may be thinking, “Wait just a minute! You want us to think about our next school year right now when we have a curriculum to teach, year-end testing on the horizon, end-of year activities to plan, and so many other things to do!”

Yes, I am suggesting that planning next year’s elementary school schedule before this school year ends is high-leverage work with huge dividends. Here’s why:

The first big idea of a professional learning community is an unwavering focus on student learning (DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, Many, & Mattos, 2016). A strategic school schedule is one that fosters student learning, that has protected instructional blocks where all students have access to Tier 1 instruction in essential knowledge and skills, and schedules blocks for special education, intervention, and enrichment. When next year’s schedule is created before the school year ends, teachers are free to plan around that schedule, and the new school year can start without a hitch.

I was hired in October as principal of Westside Elementary (a Title I school—the lowest performing school in our district, with the highest percentage of poverty and English language learners), so I did not participate in creating the school schedule that first year. As I visited classrooms, I noticed that our most challenged learners had the most fragmented school day; students were continually leaving class for interventions, missing important instruction.

I was observing in Tyler’s 3rd grade classroom at Westside. Tyler watched the clock during his teacher’s whole-class literacy instruction–unengaged, while he counted down the minutes until he left the classroom for his reading intervention. I was still in the classroom 30 minutes later when Tyler returned. His teacher had transitioned to small-group guided reading instruction while Tyler was gone.

He had missed all of the instructions for the independent literacy activities; he stood at his desk for a few moments, looking around at all the students busily engaged in learning activities. He glanced back at his teacher who was working with a small group at the reading table. Finally, he sat down at his desk and started playing with the contents of his pencil box. And whoops! His teacher had called Tyler’s reading group back to the table for instruction while Tyler was out of the room. So, here was one of our most struggling readers who missed the whole-class literacy instruction because he was clock-watching, all of the independent literacy work, and the small group reading instruction.

How could we expect Tyler to become a proficient reader when his schedule did not support his learning?

The schedule had to change, but it was so difficult to make changes after school had started. We struggled to make some minor schedule adjustments, but each item changed affected something else—a domino effect. By spring, we were carving out next year’s school schedule ahead of time. Over the next several years, we refined our process for making next year’s schedule before the end of the school year. I described the process that follows in Chapter 5 of It’s about Time: Planning Interventions and Extensions in Elementary School (Huff, 2015, pp. 111-113).

1. As student IEPs came due during the school year, we were careful to write intervention goals for special education services in 30-minute time blocks to facilitate scheduling; all interventions occurred on the hour or half hour.

2. In spring, the special education teachers prepared lists of students by grade level and content served, rolled forward to the next year so we could see how many groups would be needed in each grade level for each special education content area. Every grade-level team collaborated and agreed on a common grade-level schedule with protected instructional blocks for science (in fourth through sixth grade because science is tested in these grades), for literacy, and for mathematics.

3. Each grade level had four language arts blocks totaling 2½ to 3 hours, and two mathematics blocks: 60 minutes for instruction/practice, plus a 30-minute block for math interventions. We looked at each grade-level schedule and determined possible times when students could leave the classroom for interventions without missing instruction in essentials. Often, the grade-level schedule had to be tweaked during the process of building the schedule to make staggered intervention blocks across the school-wide schedule.

See Table I: An Example of Beginning to Build the School Schedule