Does 'All' Mean 'All?' Labels, Be Gone!

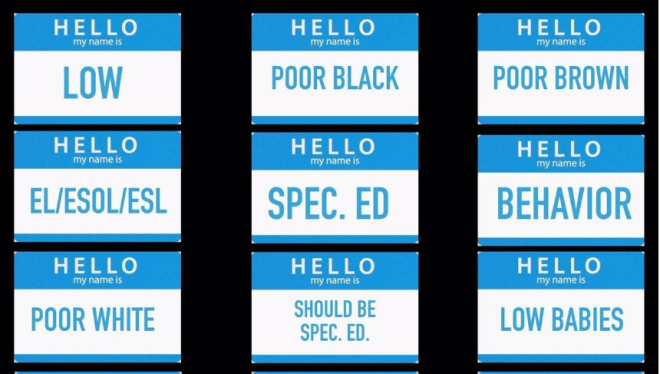

[Photo courtesy of Kenneth Williams’ Defenders and Disruptors of the Status Quo: Who Will Educators Choose To Be? (2017)]

Great teachers who truly want what is best for their students sometimes engage in this behavior.

Principals and parents who care deeply about what is best for students also engage in this behavior.

We have too, and meant no harm.

It happens and we all need to be more cognizant of the implications.

So what is this behavior?

This behavior is summing up or labeling students in one word or with phrases like the ones in the visual above.

Our assumptions drive our actions. What if we, as a profession, heeded the research from Wendy Berliner, who said “The latest neuroscience and psychological research suggest most people unless they are cognitively impaired, can reach standards of performance associated with gifted and talented” students.

What if we truly embrace advocate for and protect the following mindsets?

- We assume that all students CAN learn at high levels.

- We accept responsibility to ENSURE that all students learn at high levels—grade level or better (Taking Action, 2018).

These are often the mindsets that frame many of our district or school mission statements. How can we fully embrace these mindsets when we use terms like the ones shared above, or we say things like:

- “He is one of my high kids.”

- “I have a really low class this year.”

- “She is one of my ‘sweet and lows.’”

A few reasons why we may engage in labeling students

- We believe the label will help the student get what he/she needs. Specialized support may be provided because of the label.

- A documented diagnosis and label are often what trigger funding.

- The label helps explain low performance. It is not us, it is the student, they are not performing because they have special needs, because they are “low,” because they have a complicated home life, etc.

- We truly want what we think is best for the student–we want to help them.

While some of the reasons are valid, and may help provide services the student needs, we often find that the labels provide a convenient excuse for low expectations and performance. Instead of making excuses, we should ask ourselves how we can contribute to ensuring that each student learns essential grade-level concepts and partner with specialized service providers to ensure student success.

Why labeling can be harmful

The qualifier or label is not who the student is; it merely indicates something the student may need or identifies circumstances the student may be currently experiencing. If we are not careful, we can subconsciously attribute a set of expectations to the label. “Oh, he is a special education student, there is no way he can master that standard, we should give him something easier that he can handle,” or “she’s a really low reader, she can’t read grade-level text, let’s find text she can read instead.”

What if we provided strategies and scaffolds for students to access grade-level material instead? These scenarios play out in schools every day, and we believe they contribute to the achievement gaps that exist in most schools.

Many years ago, when we began our professional careers as educators, we both engaged in labeling students, and recall that we indeed had higher expectations for those we labeled as high achievers and lower expectations for those we labeled as low achievers. We had confidence in the high achievers and challenged them often. We had less confidence in those we labeled as low (many times unconsciously), and didn’t push them or challenge them as much.

We understand now that we were also sending an unintended message to students that we believed in them or we didn’t, and that realization was very difficult for both of us. We had good intentions. We did this because we truly cared about our students and did not want some students to unnecessarily struggle. We didn’t allow for challenge or productive struggle, in fact, we shielded them from it. We understand now that all students benefit from challenge, high expectations and productive struggle, and we do better now, but we often wish we could go back and do it all over again with high expectations for all, no matter what!

Our profession can be very difficult. We have a wide range of students with differing learning needs, and it is our job to ensure that they are all as successful as possible. As we navigate the challenge of meeting the needs of a diverse student body, we must be aware of our unconscious bias and stop looking out the window for the reasons or excuses to explain away why students may not be reaching high levels of learning. Instead, we should start looking in the mirror to determine how we can empower students to overcome obstacles and succeed despite any circumstance they face. We don’t have to figure this out alone. It's easy to get frustrated and fall into the habit of labeling students when we work in isolation and cannot tap into the collective knowledge and talents of our colleagues in a PLC at Work school to help elevate our practice and stimulate new thinking and instructional strategies.

How collaborative teams in the PLC at Work model can help us

When teachers work together on collaborative teams, focused on high levels of learning for all students, we promote feelings of collective efficacy. In other words, we believe that our actions can make a difference for our students, that with our guidance and support, all of our students will learn at grade-level expectations. As members of collaborative teams, we can remind each other that learning is our fundamental purpose. We can use evidence of learning to celebrate growth, and to determine appropriate instruction and intervention for students who need support. Together, we can determine the best ways to overcome the barriers in the way of learning for some, find student strengths and capitalize on them, and work to ensure that students are confident learners who believe they are capable.

In John Hattie’s exhaustive meta-analysis in which he ranked factors that affect student achievement, teacher collective efficacy had the highest effect size of 1.57. The average effect size is .40. This amounts to multiple years growth within a single year for students.

In the article The Power of Collective Efficacy (2018), Hattie et al wrote:

“Success lies in the critical nature of collaboration and the strength of believing that together, administrators, faculty, and students can accomplish great things. … When efficacy is present in a school culture, educators' efforts are enhanced—especially when they are faced with difficult challenges. Since expectations for success are high, teachers and leaders approach their work with an intensified persistence and strong resolve....collective efficacy influences student achievement indirectly through productive patterns of teaching behavior.”

We have both been a part of model PLC at Work schools and districts, and have witnessed the power of collective efficacy and how teachers benefit from being a part of a truly collaborative team. Being a member of a collaborative team within a PLC at Work school will give teachers access to more tools. Being a part of an effective team will make teachers mutually accountable to each other and compel educators to look in the mirror at the most important factor for that student to ensure that they focus on achieving the goal of learning for all.

What we can do moving forward

What if we walked our talk of our mission statements every day in every school for every student? We must be willing to examine our espoused beliefs and practices to determine if they match. If we say we believe “all means all,” then every action we take, every word we utter must be in alignment with that belief. We must have the integrity to protect what we believe is important. As author Brene Brown writes in her book Rising Strong (2015), “Integrity is choosing courage over comfort; choosing what is right over what is fun, fast or easy; and choosing to practice values rather than simply professing them.“

Let’s be willing to choose the courage of speaking up when we hear mis-aligned comments over the comfort of staying quiet.

Our question has been and will continue to be, “How would we want a teacher to speak about our own children?” Words have power to influence our behavior. We have the power to influence lives if we are willing to change our words, thinking, and practices. Knowing what we know now about these detrimental labels, and conversely, the power of the team doing the right work, are we willing to destroy, limit or enhance a child’s future? How will you embrace, advocate for and protect “all means all” in your work?

Labels, be gone!

References:

Buffum, Mattos & Malone (2018) Taking Action: A handbook for RTI at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Wendy Berliner, The Guardian, 7/25/17, Great Minds and How to Grow Them

The Power of Collective Efficacy, Jenni Donohoo, John Hattie and Rachel Eells, March 2018 | Volume 75 | Number 6 Educational Leadership Brown, B. (2015).

Rising strong (First edition.). New York: Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House.